In the last 10-15 years, the violence in the middle belt region of Nigeria one of the regions where Women Environmental Programme (WEP) has since inception carried out various interventions in the area of peace and security has taken a trend similar to extremist activities of Boko Haram Islamic sect. Bomb blasts and carefully planned massacres have become common place in middle belt states. It is believed that Boko Haram extremist group which before now limited their operations to the North East are strategically migrating to the middle belt region, disguising as victims of crisis in the North East and secretly wooing the youth into their extremist ideologies. It is feared that due to the ignorance of many youth, the absence of a sense of purpose, marginalization, a limited access to economic opportunities for improved livelihood and their poor economic status they may be enticed into accepting violent ideologies from unsuspecting members of Boko Haram Sect and from politicians and other individuals who may use them to pursue their causes violently.

To curtail the above, WEP in 2016 designed a project titled “Connecting Women and Youth in Violent Extremist Prone Areas through Empowerment and Skills Acquisition in Benue State.” The project received funding support from the Global Community Engagement and Resilience Fund (GCERF) a Geneva based donor. Implementation under a consortium arrangement with WEP serving as the Principal Recipient commenced in August 2016 with The Angel Support Foundation (ASF), Centre for Development and Social Justice (CEDASJ), Gender and Environmental Risk Reduction Initiative (GERRI) and the Foundation for Justice Development and Peace (FJDP) serving as Sub-Recipients on Phase I of the project which lasted from 2016 to 2019.

Our proposal and baseline had identified four major drivers of violent extremism in our context of intervention they included; ignorance, poverty, absence of opportunities and existing conflict. In Phase I, we have been able to record the following:

Ignorance: We have so far addressed the ignorance of communities on the issues of violent extremism through trainings that focused on building the capacities of community members on methods of recruitment of young women and young men into violent extremist groups, signs of radicalization and the consequences of violent extremism through our numerous trainings the project organized for local leaders, women, teachers, local religious as well as young women and young men. We were able to train community members on the general approaches aimed at PVE and the roles various community members can plan in order to prevent the recruitment and radicalization of young women and young men into violent extremism. In all our trainings reached a total of 1,242 made up of 729 men and 513 women across the four LGs of intervention. The participants have since began utilizing the knowledge gained from these trainings to initiate PVE activities within their communities.

Poverty: The project over the course of three years addressed the issue of poverty which is one of the main drivers of violent extremism in the state. The project trained young women and young men on vocational skills and provided them with start-up grants to enable them set up businesses in the various areas they acquired skills in. They have in turn continued to offer the same training they received to their peers across the various communities of intervention. These trainings have increased/improved the income and livelihood opportunities of these young women and young men. The project trained a total of 268 young women and young men made up of 134 (50%) young women and 134 (50%) young men across the four LGs of intervention who have all improved their lives and incomes and also helped other young women and young men in their communities to improve themselves.

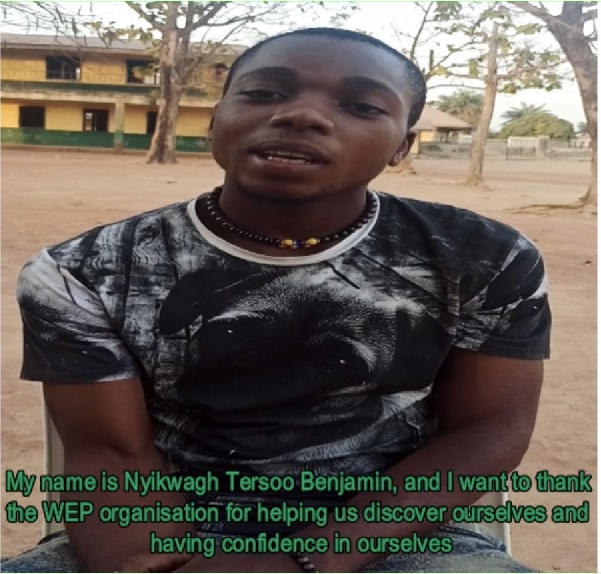

Absence of Opportunities: The project addressed the issue of the absence of economic opportunities for young women and young men which is also a major driver of violent extremism in the communities of intervention. We conducted trainings on advocacy to build the capacity of young women and young men to present their issues before local authorities. We also provided opportunities for vocational skills trainings to enable young people gain skills that will enable them become employable and provided start-up grants to enable them start-up businesses in the areas they learnt skills in. Our trainings on advocacy have enabled young women and young men across our communities of intervention to organized themselves into groups which has given them access to local leaders to articulate the issues of concern to them and their voices are been heard. The project created twelve digital/creative clubs to give young women and young men an opportunity to receive ICT skills and life skills that have boosted their lives and are

Absence of Opportunities: The project addressed the issue of the absence of economic opportunities for young women and young men which is also a major driver of violent extremism in the communities of intervention. We conducted trainings on advocacy to build the capacity of young women and young men to present their issues before local authorities. We also provided opportunities for vocational skills trainings to enable young people gain skills that will enable them become employable and provided start-up grants to enable them start-up businesses in the areas they learnt skills in. Our trainings on advocacy have enabled young women and young men across our communities of intervention to organized themselves into groups which has given them access to local leaders to articulate the issues of concern to them and their voices are been heard. The project created twelve digital/creative clubs to give young women and young men an opportunity to receive ICT skills and life skills that have boosted their lives and are

Existing Conflict: The project has been able to address the issue of existing conflict which was one of the prominent drivers of violent extremism in our context of implementation. Extremist groups before now found it easy to gain access to communities as a result of grievances from existing conflicts in such communities. These conflicts in most instances had existed for our ten to fifteen years. The project built the capacities of communities in the areas of community policing and vigilance as well as alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms. Communities are now able to resolve disputes without them escalating into violent confrontations that violent extremist groups can latch on to perpetrate violence and recruit young women and young men into their ranks. The skills gathered from the trainings have been used by communities to create community policing committees which are responsible for neighbourhood watch and liaising with security agencies to ensure that communities and their borders are secured. The project also directly intervened in conflicts through dialog

Existing Conflict: The project has been able to address the issue of existing conflict which was one of the prominent drivers of violent extremism in our context of implementation. Extremist groups before now found it easy to gain access to communities as a result of grievances from existing conflicts in such communities. These conflicts in most instances had existed for our ten to fifteen years. The project built the capacities of communities in the areas of community policing and vigilance as well as alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms. Communities are now able to resolve disputes without them escalating into violent confrontations that violent extremist groups can latch on to perpetrate violence and recruit young women and young men into their ranks. The skills gathered from the trainings have been used by communities to create community policing committees which are responsible for neighbourhood watch and liaising with security agencies to ensure that communities and their borders are secured. The project also directly intervened in conflicts through dialog ue sessions, mediations/negotiations and border meetings to help communities find lasting solutions to land disputes, communal conflicts and border disputes leading conscious efforts on the part of the government to demarcate boundaries that have been in contention for a long period of time. Our dialogue sessions, mediations and negotiations have helped communities achieve peace and mutual respect, holding dialogues and meetings on their own to find solutions to their disputes instead of resorting to violent confrontations as was the case in the past.

ue sessions, mediations/negotiations and border meetings to help communities find lasting solutions to land disputes, communal conflicts and border disputes leading conscious efforts on the part of the government to demarcate boundaries that have been in contention for a long period of time. Our dialogue sessions, mediations and negotiations have helped communities achieve peace and mutual respect, holding dialogues and meetings on their own to find solutions to their disputes instead of resorting to violent confrontations as was the case in the past.

Community Policing Committees: The project trained communities on community policing and neighbourhood vigilance. Communities from the four LGs of intervention that benefited from the trainings went back formed Community Policing and Vigilance Committees. These committees work hand in hand with local security agencies to ensur e the security of their communities and the borders of these communities. Communities who did not benefit directly from these trainings have also adopted this approach, learning from their neighbours who have adopted this approach to security. Local security personnel have attested to the effectiveness of their collaboration with these Community Policing and Vigilance Committees.

e the security of their communities and the borders of these communities. Communities who did not benefit directly from these trainings have also adopted this approach, learning from their neighbours who have adopted this approach to security. Local security personnel have attested to the effectiveness of their collaboration with these Community Policing and Vigilance Committees.

Community’s acceptance of ranching: Our initiative aimed at preventing incessant crisis between farmers and herders proposed ranching based on the recommendations of farmers and herders as a solution to the endless confrontations between them. We however initially ran into trouble in our bid to construct Pilot Mini Ranches across the LGs of intervention. Though there were consultations with communities both on the side of the farmers and the herders, communities misinterpreted the construction of pilot mini ranches to mean their land were taken from them and given to herders who are predominantly nomads. This perception was addressed through advocacy and collaborations with local administrators, community leaders, local religious and stakeholders at the community level. The subsequent construction of the pilot mini ranches has however led to communities accepting ranching as an alternative that will help prevent the incessant clashes between farmers and herdsmen.

Quarterly meetings between farmers and herders: Though the project initiated and sustained dialogues between farmers and herders to foster peaceful coexistence between them. We did not envisage the extent of acceptance that initiative received considering the years of mutual suspicion and violence between them. The dialogue sessions were not just successful but the farmer and herder communities have instituted quarterly meetings across the LGs of intervention where they meet and review issues concerning their relationship and evolve ways of settling disputes that would have otherwise escalated.

Beneficiaries of vocational skills forming themselves into cooperatives: Our Initiative on Livelihood support brought together and trained young women and young men, offering them vocational skills in areas of their interest. After receiving their grants, they have proceeded to set up businesses in their areas of interest. In a bid to foster unity and togetherness as well as provide some sort of support system for each other’s businesses, they have independently gone ahead to cluster themselves into cooperatives, contributing various amounts of money to a common purse from which members can receive soft loans to boost their businesses.

Youth advocacy groups at the LGs: The project trained young men and young women on advocacy and alternative dispute resolution mechanisms across the 4 LGs of intervention. The aim of the training was to build their advocacy and ADR skills to enable them properly articulate their issues before their leaders. The youth have across different communities of intervention formed themselves into advocacy groups which they have actively been using to pay advocacy visits on their local administrators and traditional/community leaders, engaging them on issues that matter to them.

Phase II of the project commenced in 2019 with Angel Support Foundation (ASF) and Foundation for Justice, Development and Peace (FJDP) retained as Sub-Recipients. We have also expanded from the initial four (4) local governments to six (6) Ado, Agatu, Buruku, Guma, Kwande and Logo all in Benue State where we are working to consolidate and expand the gains from Phase I in the communities of intervention.